Mahagonny Songspiel - A Concept

MAHAGONNY. EIN SONGSPIEL - CONCEPT DOCUMENT

Dr. Anthony Eversole, director

Themes

The failure of God, morality, and moral platitudes to encompass the larger and more complex aspects of the human experience.

Nihilism and Hedonism as important markers in the abandonment of meaning.

Light vs. Dark

Acceptance of self over restrictive societal conventions

The emergence of the outsider as the insider

Investigation and skepticism of prior societal and moral conventions.

The embrace of protest against systemic injustice, no matter the source.

Acceptance of sexuality and sex-positivity

Shame resilience and vulnerability on display for an entire like-minded society; safe individualism

The dark and light aspects of Utopianism. (dystopian left vs. utopian right)

The temporary nature and artificiality of the "golden age" - The golden age as a metaphor for youth.

Mahagonny

Mahagonny, Bertold Brecht's dream city dystopia was clearly influenced by Weimar Berlin. The social commentary of the city that was in the midst of a post-war financial crisis, a rapidly emerging sex-trade, an embrace of outsiders of all types, a rapidly developing dance hall and cabaret scene, and a new movement in art, music, and architecture that was increasingly un-emotional and nihilistic found its place in Weill's collaboration. Mahagonny's six-scene structure explores great enthusiasm for the proposed utopia, followed by tragedy.

Four men arrive with traveling cases, and sing of their intention to travel to Mahagonny, where everything is beautiful.

Two girls enter. They too are disillusioned with their old world, and hope to find material happiness in Mahagonny.

The four men enter, smoking and drinking. They complain of the high cost of living in Mahagonny, and play a game of poker.

The men and girls meet in a bar in Mahagonny. Life in the city has not come up to expectations. They wish to go somewhere else – Benares for instance. But they open their newspapers and read that Benares has been destroyed.

One of the men, Jimmy, plays the symbolic role of “God” in Mahagonny: symbolic not so much of divine authority, or even of guilty conscience, as of man-made authority. That is to say “man creates his gods in his own image.” The other inhabitants of Mahagonny threaten the “new” arrival, and he, after questioning them, orders them to Hell. But they revolt and say they are already there.

Protest marches are staged in Mahagonny, and the city goes up in flames: the plunderers are plundered. As the curtain falls, one of the girls tells the audience that there is no such place as Mahagonny.

Weimar Berlin 1919-1933

The Weimar Republic is the unofficial name given to Germany in the interwar period from 1919 to 1933, between the defeat of Germany in the Great War in 1918 and Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. During that time, Berlin became the intellectual and creative centre of Europe, doing pioneering work in the modern movements of literature, theatre and the arts, and also in the fields of psychoanalysis, sociology and science. Germany’s economy and political affairs were suffering at the time, but cultural and intellectual life was flourishing. This period in German history is often referred to as the ‘Weimar Renaissance’ or the country’s ‘Golden Years’.

Dubbed the ‘Babylon of the 20s,’ the city centre flourished with youthful activity and explosive sexual freedom. Provocative cabaret shows, excessive drug use, nights of hedonistic partying, open and same-sex relationships all took centre stage in Berlin. There were many strong women in the movement, with performers such as Marlene Dietrich and Anita Berber becoming icons of the time in their lifestyle, art and relationships. It was also the decade of Brecht, Weill, the Isherwoods and the Bauhaus movement in art and design.

In the documentary entitled Metropolis of Vice, Legendary Sin Cities, which offer a snapshot of the times, we hear that, ‘Berlin was what sexual daydreams wanted to be. You could find almost anything there, and maybe everything.’ This kind of creative freedom of thought and expression was a revelation, and an offense to the austere and conservative extreme right wing that was on the rise, namely Hitler and his Nazis.

Post-War Financial Collapse

The Treaty of Versailles (ratified in 1919) compelled the Central Powers to pay war reparations to the Allies. Germany was required to pay equivalent to $33 billion in contemporary values. These reparation requirements destroyed the new Weimar Republic's financial stability and German currency lost all value. There are several references to "finding the next dollar" in Mahagonny. This was a reality of the times. In the later 1920s, there was an influx of foreign money which nourished the dance hall culture for which the Weimar Republic is known.

Dance Hall and Cabaret Culture in 1920s Weimar Berlin

Cabaret was a form of live entertainment, popular in German society in the 1920s. Often depicted in art and film, Weimar cabaret became known for its colour, freedom and decadence. Cabaret performances often contained political ideas or undertones.

Cabaret probably reached its zenith during the so-called ‘Golden Age of Weimar‘. This period between 1925 and 1929 has become known for its high living, vibrant urban life and the popularization of new styles of music and dance. (Mahagonny premiered in 1927 - in the midst of these Golden Years)

Having previously lived under an authoritarian monarchy, where entertainment and social activities were tightly regulated, many Germans thrived on the relaxed social attitudes of the late Weimar period. The influx of foreign money and the economic revival of the later 1920s also encouraged celebration, spending and decadence.

After World War I, cabarets became enormously popular across Europe. Nowhere were they more popular than Germany. The Weimar government’s lifting of censorship saw German cabarets transform and flourish.

Entertainment in the cabaret of Berlin, Munich and other cities often revolved around two themes: sex and politics. Stories, jokes, songs and dancing were laced with sexual innuendo. As the 1920s progressed, this gave way to open displays of nudity, to the point where most German cabarets had at least some topless dancers.

Some cabarets were also patronized by homosexual men, lesbians and transvestites. Previously forced to conceal their sexuality, these individuals seized upon the relaxed liberalism of the cabaret scene to openly display and discuss it.

According to some historians, this extravagance may have been driven by a realization that this ‘Golden Age’ was both artificial and temporary. Many Germans spent big and partied hard, they argue, as they were aware this prosperity would not last. Brecht and Weill make this a central theme in Mahagonny.

The Political Reaction to 1920s Weimar Cabaret Culture

The late Weimar era was marked by liberal ideas as well as new forms of cultural expression, entertainment and hedonism (pleasure-seeking).

Weimar music, dance and entertainment were criticised by radicals on both sides of politics. Socialists believed it represented the wastefulness of capitalism; right-wing groups and reactionaries claimed it was evidence of weak government, moral decay and corruption.

As might be expected, German conservatives, reactionaries and wowsers loathed the cabarets. They were regularly criticized in the press and from the pulpits of Germany’s Catholic and Lutheran churches, though this did little to diminish their popularity.

Right-wing political groups like the National Socialists (NSDAP) routinely attacked the cabarets, even though many of their members and some of their leaders were seen there. They painted the cabarets as corrupt melting pots, filled with racial and ethnic groups as well as dangerous political and social ideas.

Weill's Hybrid Sound-World

Weill was heavily influenced by the Jazz Age, and throughout his career he bridged the gap between classical concert music and popular dance hall styles. His marriage to popular singer Lotte Lenya and collaborations with Bertold Brecht pushed the hybrid style even further into what would become known as quintessentially "Weill".

Weill's First Collaboration with B. Brecht

Mahagonny was the first of many Brecht/Weill collaborations, including the very famous Dreigroschenoper (The Three-Penny Opera), an adaptation of John Gay's The Beggar's Opera and with songs that have become standards, such as "Die Moritat von Mackie Messer" (The Ballad of Mack the Knife) and "Seeräuberjenny" (Pirate Jenny) - Mahagonny has its own popular standard in "Alabama Song" which has been covered by The Doors and David Bowie, among others.

The Sex Trade in Weimar Berlin

Due to the deregulation of prostitution and fiscal collapse after the war, the sex-trade and sex-positivity boomed in Weimar Berlin.

The sex reform movement of Weimar Germany (1919-1933), was dedicated to providing more sexual and, in turn, social freedoms to men and women. Its two major aims were to give working class men and women access to information about and means of birth control and to reform the Paragraphs 218 and 219 of the German Penal Code of 1871 that prohibited abortion and the help for it.

Women’s liberation by access to birth control and the right to control their own body was not the only aim of the sex reform movement, another was the recognition of all forms of sexuality including homosexuality. In July 1919, the Institute of Sexual Research (Institut für Sexualwissenschaft ), the first of its kind, was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld (1836-1935). Hirschfeld was a German Jewish physician and sexologist with a practice in Berlin-Charlottenburg, who had founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, WhK) in Berlin already in 1897, to campaign for social recognition of gay, bisexual and transgender men and women, and against their legal persecution. The Institute of Sexual Research educated the public with the aim of a better understanding of sex and sexuality as a whole and offered in-depth education on the topic. The rise to power of the Nazi Party in January 1933 ended the movement. Many of its supporters were persecuted by the Nazis and imprisoned or had to migrate.

The fight for a reform of the regulation of prostitution also emerged as part of the struggle for sex reform during the Weimar Republic with the aim to prevent the persecution of the women. While other countries were cracking down on prostitution by declaring it to be a sexual crime, the welfare state of Weimar Germany began decriminalizing it by implementing legislation like “The Law for Combatting Venereal Diseases,” passed in 1927. These laws required that doctors begin treating women who came in with sexually transmitted diseases, even prostitutes, without persecuting them.

Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity)

The post war artistic movement was a criticism of the previous expressionism and repudiation of the war. Brecht, in particular, was a vocal critic of expressionism, referring to it as constrained and superficial. Just as in politics Germany had a new parliament but lacked parliamentarians, he argued, in literature there was an expression of delight in ideas, but no new ideas, and in theater a "will to drama", but no real drama. His early plays, Baal and Trommeln in der Nacht (Drums in the Night) express repudiations of fashionable interest in Expressionism.

Rejecting the notion of centering art around their own inner turmoil like the expressionists. the artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit rejected the self-involvement and romantic longings of the expressionists. Weimar intellectuals, in general, made a call to arms for public collaboration, engagement, and rejection of romantic idealism.

Hans Holbein's Dance of Death Woodcuts

The Dance of Death by the German artist Hans Holbein (1497–1543) is a great, grim triumph of Renaissance woodblock printing. In a series of action-packed scenes Death intrudes on the everyday lives of thirty-four people from various levels of society — from pope to physician to ploughman. Death gives each a special treatment: skewering a knight through the midriff with a lance; dragging a duchess by the feet out of her opulent bed; snapping a sailor’s mast in two. Death, the great leveller, lets no one escape. In fact it tends to treat the rich and powerful with extra force. As such the series is a forerunner to the satirical paintings and political cartoons of the eighteenth century and beyond. For example, Death sneaks up behind the judge, who is ignoring a poor man to help a rich one, and snaps his staff, the symbol of his power, in two. A chain around Death’s neck suggests he is taking revenge on corrupt judges on behalf of those they have wrongfully imprisoned. In contrast, Death seems to come to the aid of the poor ploughman, by driving his horses for him and releasing him from a life of toil; the glowing church in the background implies this old man is on his way to heaven.

Holbein drew the woodcuts between 1523 and 1525, while in his twenties and based in the Swiss town of Basel. It would be another decade before he established himself in England, where he painted his most enduring masterpiece The Ambassadors (1533), in which two wealthy, powerful and worldly young men stand above (and oblivious to) an anamorphic skull that signals the ultimate vanity of all that wealth, power and worldliness. In the 1520s, Holbein was busy trying to earn a living in Basel, painting murals and portraits, designing stained glass windows, and illustrating books. The year before he began The Dance, he had illustrated Martin Luther’s influential translation of the New Testament into German. So Holbein was working close to the heart of the accelerating movement for Church reform. It comes as little surprise, then, that Death reserves particularly grim treatment for members of the Catholic clergy. It drags off a fat abbot by his cassock, leads an abbess away by the habit as though she were an animal, and takes the form of two skeletons and two demons to see to the pope himself.

Holbein’s woodcuts were a highly original take on a medieval theme. Death had first been seen dancing in Europe in 1425, on a mural at the Paris Cemetery of the Holy Innocents. From there it had jigged its way across Europe, onto more walls (including two in Basel cemeteries) and book reproductions of them. In Holbein’s series no one is actually engaged in a dance with Death. This removes an element of comic catharsis found in the mutuality of earlier dances. Holbein’s more static figures respond to Death realistically. The old man is stoical. The panicked knight fights with all his useless might. The rich miser throws up his arms in a mix of outrage and terror. The peddler is almost too busy to even acknowledge his time has come.

Holbein’s achievement is the greater because of the miniature scale he was drawing in. Reproductions obscure just how tiny the wooden blocks were — no bigger than four postage stamps arranged in a rectangle. The blocks were cut by Hans Lützelburger, a frequent and highly skilled collaborator of Holbein’s. Lützelburger had cut forty-one blocks and had ten remaining when Death surprised him too. The blocks were then sold to creditors, and eventually printed and published for the first time in Lyons in 1538 as Les simulachres and historiees faces de la mort. Since the book's great success Holbein’s series has been consistently in print, inspiring writers and artists from Rubens in Flanders, to Millet in France, and Dickens in England. Penguin Classics recently published an excellent edition which includes much helpful historical context from Ulinka Rublack.

Director's Note: In his production notes, Weill scholar David Drew declared Mahagonny to be a Totentanz. This led me to explore some non-Weimar-era art that still fits with the themes and visual language of our production. I found these to be visually pleasing and extremely on-brand.

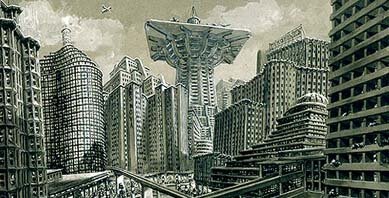

Fritz Lang's Metropolis

Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis is the tale of a utopian city (Mahagonny) that is built upon forced labor from a lower class. The dichotomy of technology vs. humanism is explored. The film was released the same year as the opera and I found the visual style (and the obvious color palette) to be appropriate. This also led me to the idea of using silent film visual title imagery for the the signs and placards on either the surtitles, the protest signs, and other physical signs as listed in the original production notes. The imagery of death is something our theme shares with the Holbein art.

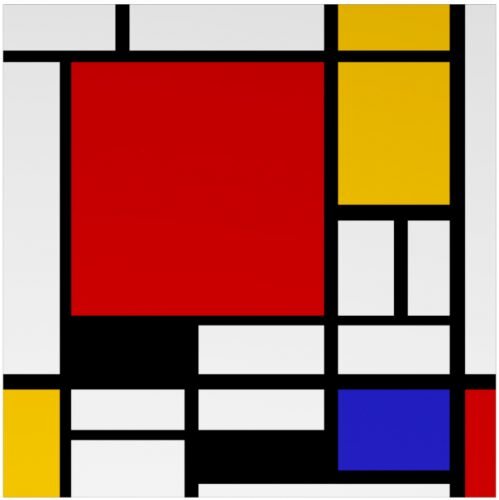

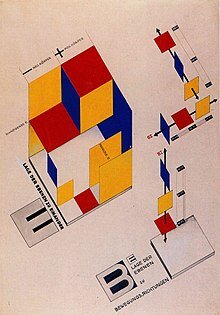

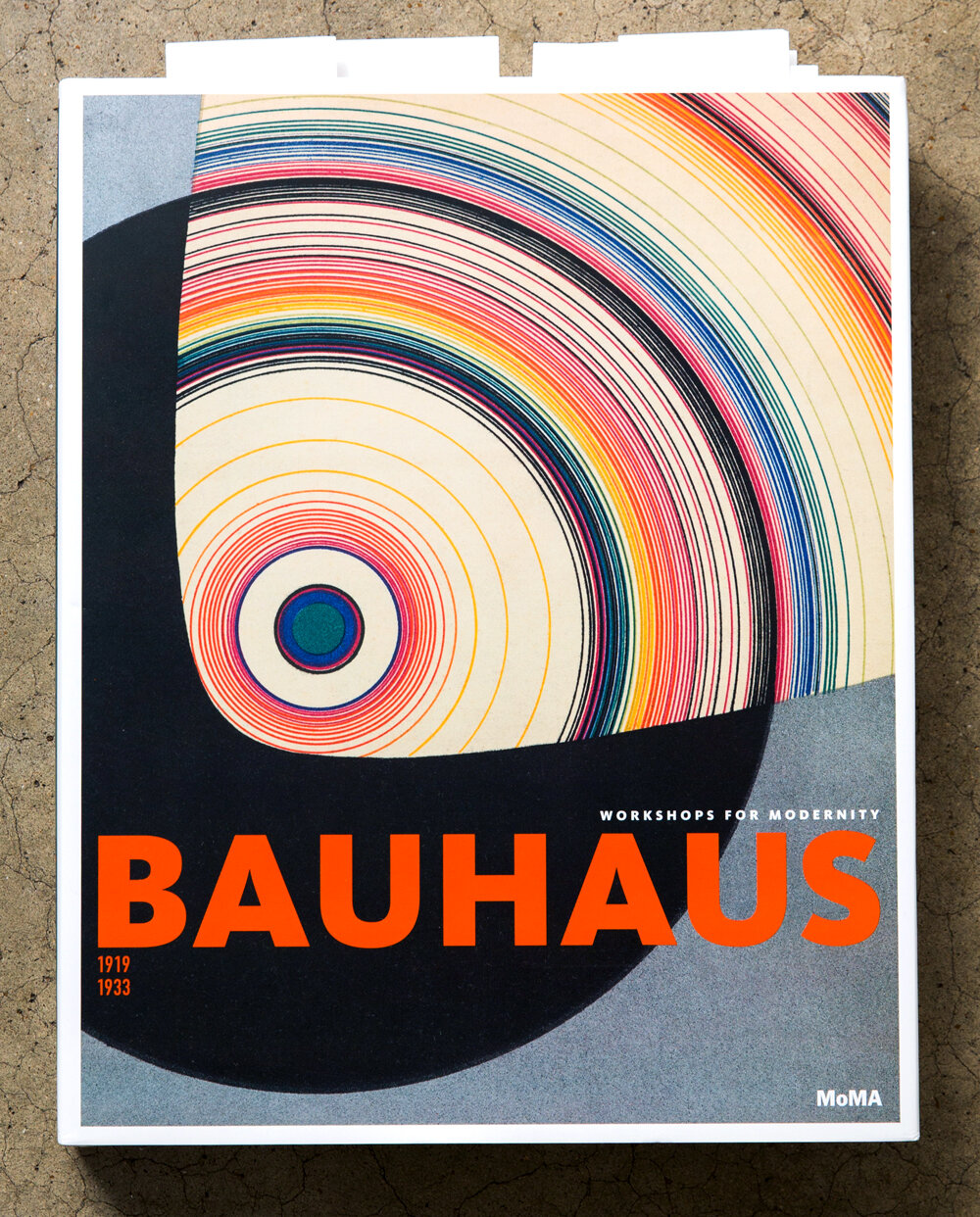

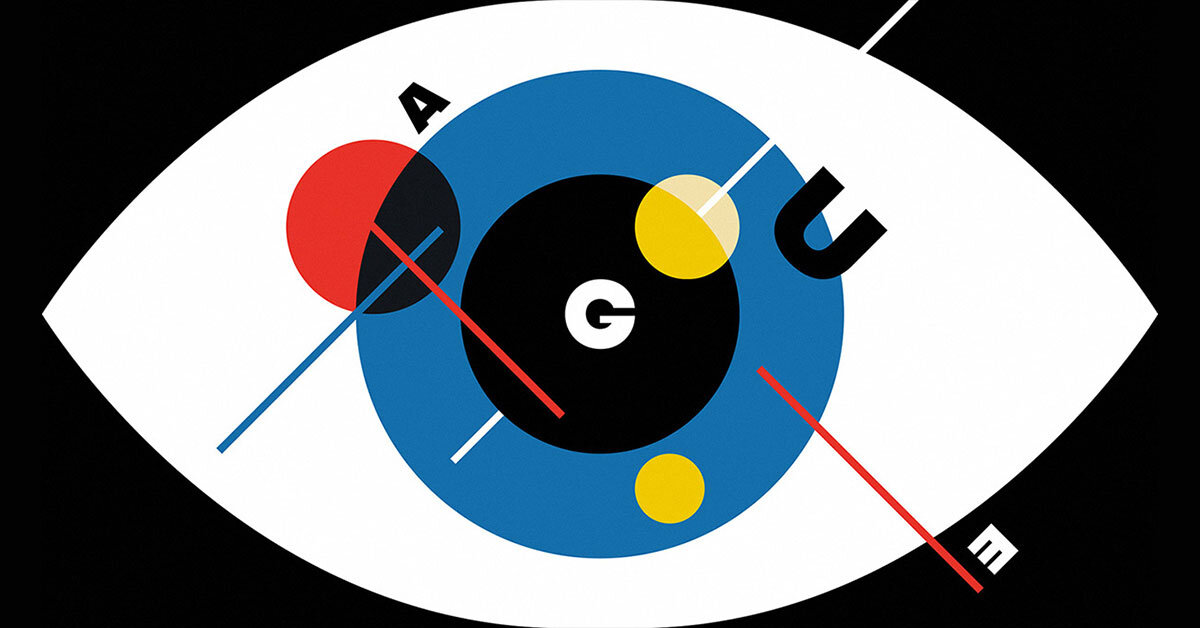

Bauhaus

Bauhaus design and architecture: simplicity and function over form and ornamentation. A very specific color scheme and a profound effect on graphic design.

Christopher Isherwood's Goodbye to Berlin

Goodbye to Berlin is a 1939 novel by Anglo-American writer Christopher Isherwood set during the waning days of the Weimar Republic. The work has been cited by literary critics as deftly capturing the bleak nihilism of the Weimar period. It was adapted into the 1951 Broadway play I Am a Camera by John Van Druten and, later, the 1966 Cabaret musical and the 1972 film.

The novel recounts Isherwood's 1929-1932 sojourn as a gay pleasure-seeking British expatriate in poverty-stricken Berlin during the twilight of the Jazz Age. Much of the novel's plot details actual events, and most of the novel's characters were based upon actual people. The insouciant character of Sally Bowles was based on teenage cabaret singer Jean Ross. The novel was later republished together with Isherwood's earlier novel, Mr Norris Changes Trains, in a 1945 collection entitled The Berlin Stories.

Sally Bowles

As mentioned above, the character was based cabaret singer Jean Ross. She was made an icon by the Kander/Ebb musical and especially by Liza Minelli. The musical's depiction of Sally Bowles was modeled from the iconic look of Louise Brooks, with a little Marlene Ditrich mixed in.

Liza Minelli az Sally Bowles in Cabaret

Louise Brooks

Mary Louise Brooks (November 14, 1906 – August 8, 1985), known professionally as Louise Brooks, was an American film actress and dancer during the 1920s and 1930s. She is regarded today as a Jazz Age icon and as a flapper sex symbol due to her bob hairstyle that she helped popularize during the prime of her career.

Marlene Dietrich (Lola Lola from The Blue Angel)

27 December 1901 – 6 May 1992) was a German-born American actress and singer. Her career spanned from the 1910s to the 1980s.

In 1920s Berlin, Dietrich performed on the stage and in silent films. Her performance as Lola-Lola in Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (1930) brought her international acclaim and a contract with Paramount Pictures. Dietrich starred in many Hollywood films including, most iconically, the six vehicles directed by Sternberg. Dietrich spent most of the 1950s to the 1970s touring the world as a marquee live-show performer.

The Color Palette

Blacks, whites and grays with other muted tones. This will combine with the concept of using seance photographs as the visual inspiration for the Medium. Contrasts with a single accent color. Perhaps red.

Another idea is using the Bauhaus color scheme with the blacks, whites and muted grays for a bolder adaptation. I'm open to seeing either implementation.