Amélie: La couleur de l'etrangete

The Jeunet Aesthetic

Jean-Pierre Jeunet is a self-taught director with a predilection for a fantastic style of cinema where form and color are as important as the subject and plot. His film Amélie was praised for its feel-good quirky story, its production design, specific color palette, and unique cinematographic approach.

The narrative, characters, and production design of Amélie are geared towards giving the film a very distinctive “fairy tale” atmosphere that further informs its romantic qualities.

In a conversation about his love for the fairy tale aesthetic and production design in his films, he said:

I like the cinema of people like Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton. I am not keen on trying to reproduce reality - for that you should do documentaries.

The lack of imaginative aesthetics and creative production design is one of Jeunet’s qualms with the French film industry. Jeunet said:

This is one of the things I don’t like so much about French cinema - we have a tendency to concentrate on actors and dialogue and we don’t care so much about the visual aspect. I love when you use all the elements at your disposal.

Jeunet certainly uses all the aesthetic tools available to him. Tools such as fourth wall breaking, PoV camera shots, the use of a scrupulously specific color palette, and a creative sense of framing creates a removes world that give the audience a sense of voyeurism. They are not part of the world, but are interfering in these people’s lives (similar to what Amélie does in the story).

The color scheme of greens and reds with accents of yellow is consistent throughout the entire film. There is an idealism and fairy-tale quality to the color scheme which relies on mono-chromaticism to idealize Jeunet’s quixotic take on Paris.

Amélie’s Paris is representational. Her world merely represents Paris.

Juarez Machado

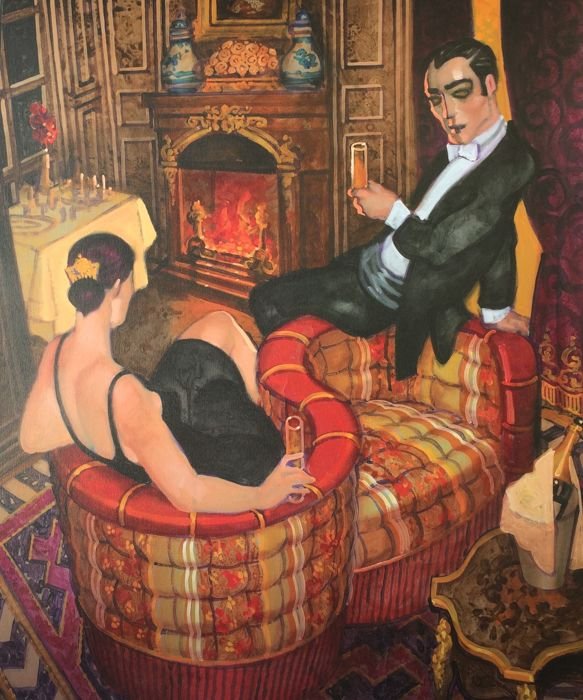

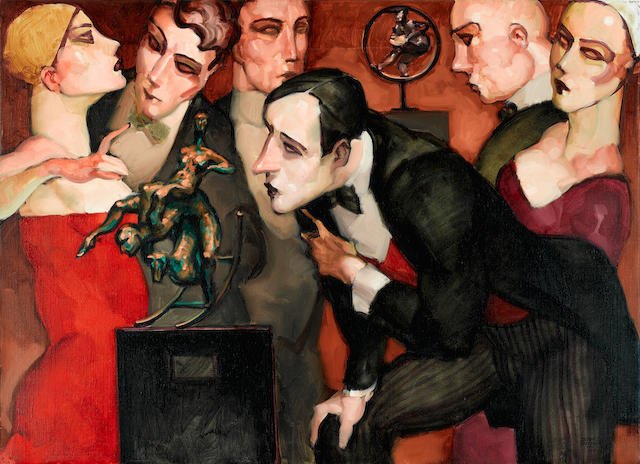

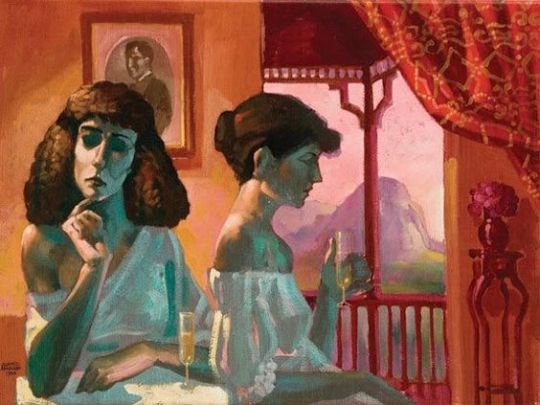

The primary influence on Jeunet’s monochromatic approach is Brazilian painter (living in Paris) Juarez Machado. Similar to Jenuet’s production design, Machado employs two principal hues (often red is among them) and one lesser accent color. He frequently works monochromatically to create stories of idealism, happiness, and passion. Similar to Jeunet, Machado’s colors are always heavily saturated. Check out some of Machado’s art below:

Red

Red represents Amélie’s life and mood. Red is the color of warmth, life, energy, and passion. Though Amélie was raised without understanding love, she has much to give. She must observe others to learn to establish loving relationships and find connection and belonging in her life.

Green

Green is the color of new beginnings and growth. It also is an important color for Jeunet’s Paris. Much of Amélie’s story revolves around the Paris Métro (Metropolitain) and green is a significant color for the city’s history, and especially that of the Métropolitain.

In the years leading up to the Exposition Universelle, a World’s Fair held in 1900, Paris was busy building the Métropolitain, or Métro, a new public transit network. In order to make the above-ground components of this new underground system as aesthetically pleasing as possible, the Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris, or Paris Metropolitan Railway Company, commissioned Hector Guimard to design entryways that were “as elegant as possible.”

“Édicule” (kiosk) Entrance

In order to meet this criteria, Guimard opted to craft his entrances out of cast iron set in concrete and painted a shade of green evocative of oxidized brass. The use of cast iron allowed him to construct the curved forms characteristic of his style, and concrete enabled him to incorporate sculpted details throughout each design—whether rendered as a roofed édicule structure or an open entourage model.

“Entourage” Entrance

Guimard's édicule (“kiosk”) metro entrance features a fan-like awning made of glass. Undoubtedly inspired by the delicate wings of a dragonfly (one of Art Nouveau's major motifs), this style epitomizes the movement's interest in reinterpreting organic forms as functional objects. Today, only two original édicule entryways exist in Paris.

The other type of Guimard-designed entryway is known as entourage (“enclosure”). This genre features two serpentine, stem-like lamp posts joined by an equally sinuous arch. Each stalk is topped with a glowing red orb reminiscent of either an insect's eye or a flower bud.

Both the édicule and entourage entryways are adorned with either “Métropolitain” or “Métro,” rendered in a typeface that has come to represent Art Nouveau.

See below for examples of Jeunet’s monochromatic green palette in Amélie, many of these shots use Guimard’s artificial bronze patina motif throughout the metro.

Yellow

While yellow is not nearly as prominent as red and green in Jeunet’s production design, it does make a dominant appearance in important moments of discovery and change. When Amélie discover’s the tin box that was hidden by Bretodeau as a child, we are shown her predominantly yellow bathroom. Again at the end of the film during the vespa ride with Nino, we see a significant life change introduced with the accent hue. Yellow becomes a color of hope, connection, and belonging. The audience also sees yellow when Amélie is engaged in service, such as with the blind beggar and Dufayel.

Blue

Blues are almost non-existent in the film until the introduction of Nino Quincampoix. We first see the blue in the photo booth where Nino is searching for torn photos. Thereafter we get occasional (and quite intentional) accents of blue. It garners the audience’s attention because it is always a deeply saturated hue and a deviation for the established use of color in the film. Nino introduces new color into Amélie’s world. She is then able to seek a life with connection, love, and belonging.

The Narrative Power of Color

From V Renee’s blog on the narrative power of color (nofilmschool.com)

First of all, our emotional responses to colors depend on several different factors. Cultural norms, traditions, and personal experiences change the significance of colors and their meanings for every individual. For example, American's might feel a sense of patriotism, pride, or bravery when viewing the colors red, white, and blue, while a citizen of Ghana or Portugal may feel that way when viewing green, red, and gold.

Contextually, colors change their effects based on the situation they're appearing in. Red, for example, may signify "love", "passion", and "intimacy" when it's shown within the context of a romantic encounter, but if it's shown during a fight sequence or highly suspenseful scene it could signify "danger", "blood", and "death".

Despite the fact that emotional responses to colors varies greatly based on culture and context, there are fairly universal interpretations for many colors, which is visualized in Plutchik's Wheel of Emotions below:

We perceive color not only on an emotional level, but on a physical and psychological level as well. This episode of PBS' Off Book offers an interesting perspective:

Color has the potential to create a tone, change the meaning of a scene, and alert our audience to something important on the stage or in the story. It's not solely an aesthetic tool -- it's a narrative one. Understanding how our audience will respond emotionally to different colors can add so much dimension and depth to our story, all without having our characters speak or sing a single word.

Next post I’ll talk more about Amélie’s Paris, scenic considerations, ornamental design, and structuring the scenic elements around the storytelling as well as the visual style.

Until then,

A