Amélie: Guimard, Art Nouveau, and the Scenic Aesthetic

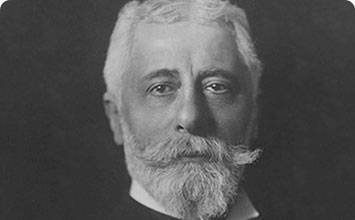

Hector Guimard

Hector Guimard

“For construction, do not the branches of the tree, the stems, by turn rigid and undulating, furnish us with models?”

-Hector Guimard

Hector Guimard practiced what he preached. His architectural creations tend to embrace each of the different branches of the arts, from painting and sculpture to graphics and even typography. The seamless harmony and flow that reigns in the aesthetic of Guimard's buildings and other works very much mirrors the kind of harmonious environment and society that Guimard hoped the world could eventually achieve politically, though this never came to pass. Guimard's version of Art Nouveau was nationalistic (he was French), but also focused on community and the friendly acknowledgement of differences between the varied nationalities and ethnicities of the world. Today Guimard is regarded as one of the most individualistic artists of his era, one of the innovating founders of Art Nouveau who developed a personal aesthetic that is often instantly recognizable and distinguishable even from his fellow practitioners of the style.

Accomplishments of Guimard

Guimard is by far the best-known French Art Nouveau architect, to the extent that in some French circles Art Nouveau was referred to as "Style Guimard," a moniker promoted by Guimard himself. His work is easy to distinguish amongst other practitioners of the style, with plastic, abstracted and sometimes bizarre vegetal and floral imagery in iron, glass, and carved stone that is usually twisted and bent into irregular and asymmetrical forms.

Though well-educated at the École nationale des arts décoratifs, and familiar with many of the leading French architectural theorists, Guimard attended but did not receive a diploma from the École des Beaux-Arts as was the norm for most French academic architects at the end of the 19th century, and was often thought of during his lifetime as outside the mainstream of architectural practice.

Guimard's work has recently been discovered to be rather political - particularly pacifist and socialist. The strange forms in his architecture are intended to function as great kinds of social levelers, favoring no social or economic class above any other in terms of their familiarity or ability to be interpreted. As a result, they also constitute a step towards artistic abstraction, one of the great developments of 20th-century modernism.

Guimard's Paris Métro entrances are his signature work and classic emblems of Art Nouveau, which combine the movement's embrace of nature as well as the advances of technology, standardization, and modernization. Their sinuous, unusual forms stand out against the typical street environments, making them ideal for their functions, and they have become worldwide icons for mass transit design.

Entrances for the Paris Métropolitain

When Guimard was commissioned to design what would become his signature work, Paris was only the second city in the world (after London) to have constructed an underground railway. Guimard's design answered the desire to celebrate and promote this new, efficient infrastructure with a bold structure that would be clearly visible on the everyday Paris streetscape. Guimard was awarded the commission as a favor from the Socialist-controlled Paris City Council, whose political leanings mirrored his own sympathies.

The Métro connects with themes of Socialism and industry on several levels. Guimard used the industrial materials of cast iron for the structures of the entrances - a nod, no doubt, to the industrial workers who used the system for their commute and helped build the network. Guimard created three standard types of entrances: enclosed, tripod canopies, and open to the sky - that use the twisted, organic vegetal forms typical of Art Nouveau. At first, these appear to be nearly seamless, yet in fact they are constructed out of several cast iron parts that were easily mass-produced at the modern iron foundries to the east of Paris. The possibilities of cast iron were shown off in two unique elaborate enclosed pavilions, located at the busy stations Bastille and Etoile, which were often nicknamed "Chinese pagodas" due to their resemblance to eastern architecture. In another modern twist, the red bulbs that illuminated many of the entrances at night also pulsated upon the arrival of a train to alert potential users at street level. Guimard even invented the typography used for the yellow porcelain signs hung between the lamps, a typeface that has now famously become known as Métropolitain.

But the Métro entrances' forms do much more than make smart use of modern technology. Guimard conceived of the Métro as a means to connect people residing in different geographic parts of the city and across social classes and backgrounds - especially since Paris has traditionally been a favorite destination for immigrants and foreign travelers. The sinuous stem, seed-pod, and bulbous forms of nature Guimard employs are unrecognizable as any particular species, in effect making them great levelers of all who use the network, as they are universally incomprehensible - save for the "M" cleverly worked into the seed-pod shields in the railings. Guimard's designs were thus instrumental in bringing Art Nouveau's otherwise complex designs to a mass audience for whom the style seemed like a symbol of unattainable luxury (a function that it arguably still fulfills today). They helped combat the notion that Art Nouveau was a style destined only for a wealthy clientele who could afford lavish and labor-intensive constructions.

For all their attempts at unity, the Métro entrances nonetheless represent one of the most noteworthy examples of the French backlash against Art Nouveau. As early as 1908, Guimard's entrances were removed from the Champs-Elysees because they did not "harmonize" with the classical buildings there. Demolition of individual entrances continued through the 1960s, with the Etoile pavilion removed in 1926 and the Bastille station in 1962. With the retrospective recognition of Guimard's artistic genius, however, the remaining 88 entrances have been protected by the French state since 1978. Moreover, the physical dissemination of Guimard's entrances to different cities across the world and their functional installation there means that his designs have become universally synonymous with the idea of mass transit. In this sense, they finally fulfill Guimard's dream of linking people across political, social and economic boundaries, on an even broader level than he may have ever imagined.

Métropolitain Interiors

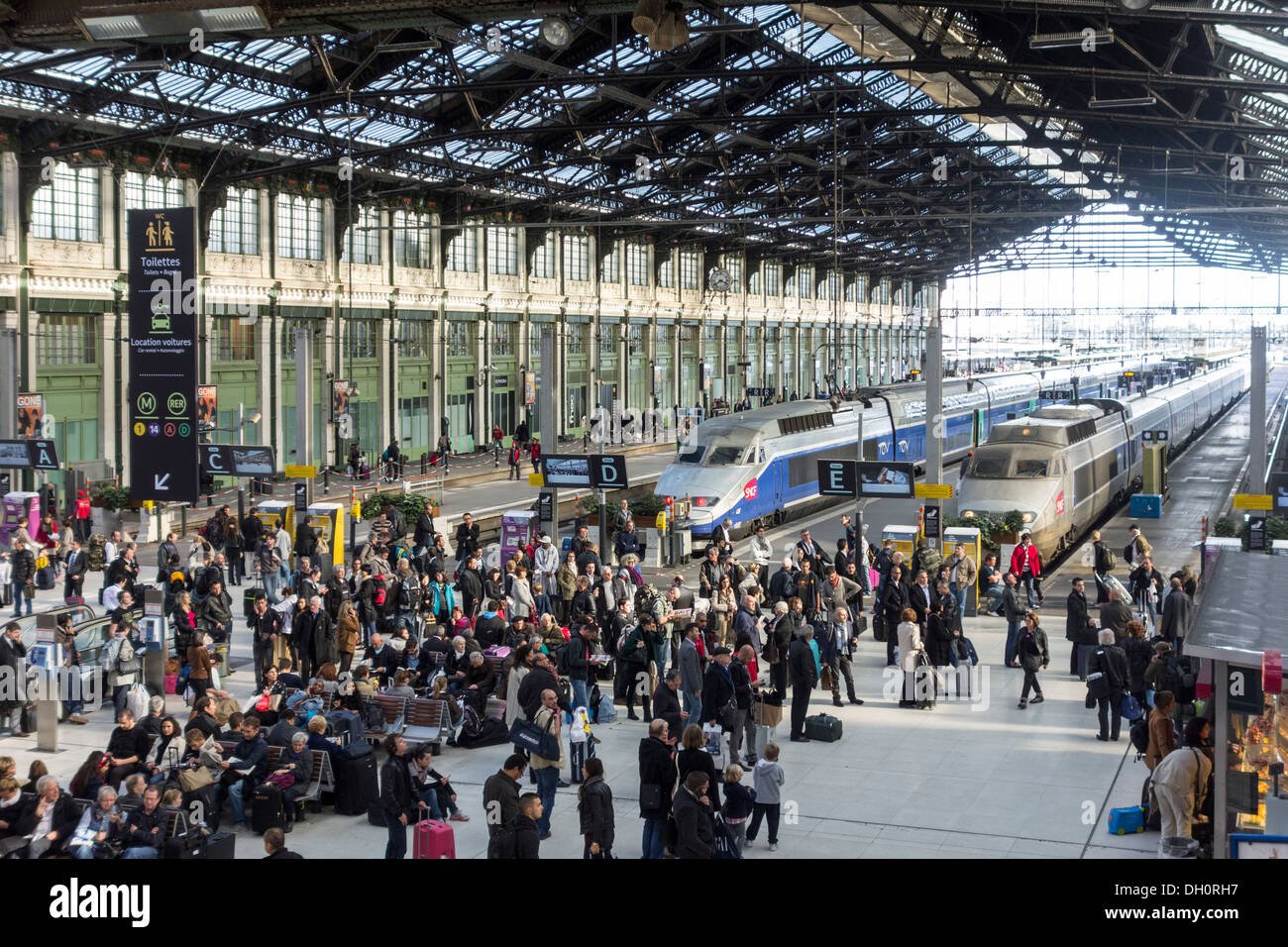

In exploring interiors of some of the metro stations featured in Amélie, we come across beautiful die-cast ornamentation as well as structural criss-cross bracing, which I see as being a potential thematic visual device. It is very Parisian (see the detail images of the Eiffel Tower as well) and emphasizes the need for strength and stability in architecture and human connection. The criss-cross bracing is metaphorical of arms reaching out to support one another with connection and providing belonging. This is the central theme of Amélie.

Pay attention also to the “riveted” aesthetic which also lends a conceptualization of stability. The clocks at Gare de Lyon are a beautiful accent and could be a potential scenic landmark. They also fill a thematic with the recurring “how to tell time” musical motif.

Gare de Lyon

Gare de L’Est

The windows at Gare de L’est are another potential scenic landmark ripe for borrowing.

Other Parisian Ornamentation

The criss-cross bracing, riveted, and die-cast ornamentation (a la Guimard) can also be seen throughout Paris. See the gallery below.

Cafe de Deux Moulins

The café/bistro where Amélie works is a real establishment that was used in the shooting of the film. The Café des 2 Moulins (French for "Two Windmills") is a café in the Montmartre area of Paris, located at the junction of Rue Lepic and Rue Cauchois (the address is 15, rue Lepic, 75018 Paris). It takes its name from the two nearby historical windmills, Moulin Rouge and Moulin de la Galette. See images below.

More Images from Montmartre

Amélie lives and works in Montmartre. Just down the street from the historic Sacre Coeur. See below for images of the area. The idyllic cobblestone streets paired with bistro awnings and sidewalk cafés create a feeling of Jeunet’s idealized Paris.