Leoncavallo, Zazà & The Giovane Scuola

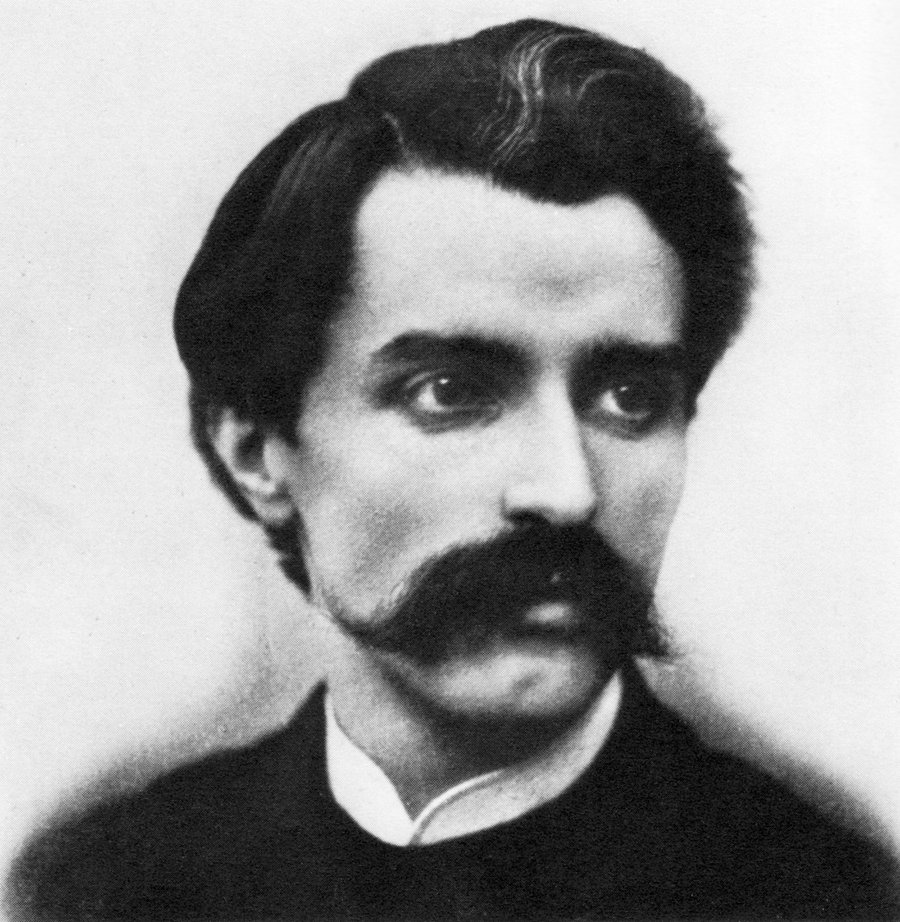

Giuseppe Verdi

The world of Italian Opera during the 19th century was dominated by Giuseppe Verdi. As Verdi aged, however, his operatic output became growingly sparse with long gaps between the releases major works. Naturally, with the importance of the art form to Italian culture at the time, other composers rose up to fill the void of Italian opera left by the Maestro Verdi.

The most prominently revered today is Giacomo Puccini, who began seeing success in the 1880s. His early success overshadowed his contemporaries during the final decade of the century with such hits as Manon Lescaut (1893), La Bohème (1896), and Tosca (1900). Laura Protano-Biggs writes that “Puccini can be best understood as just one member of a wider circle of composers born at mid-century who created a new and distinct soundscape. These composers all operated in Milan between the years of 1880 and 1900 and were dubbed the ‘giovane scuola’ or ‘young school.’

The giovane scuola consisted of Puccini, Alfredo Catalani, Alberto Franchetti, Pietro Mascagni, Francesco Cilea, Umberto Giordano, and Ruggiero Leoncavallo.

The Giovane Scuola

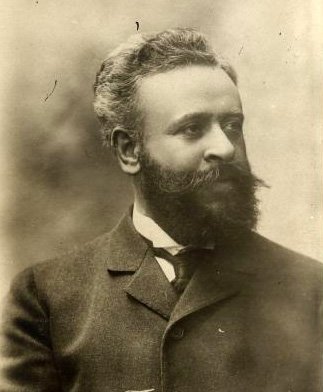

Leoncavallo’s Early Life and Music

Though Leoncavallo’s autobiographical notes were greatly exaggerated when compared to the facts, musicologists have been able to decipher most of the fact from the fiction.

Leoncavallo was born in Naples in 1857. His father was a judge (the plot of Pagliacci is reported to be a true account of a case over which his father presided.) In his teens, he enrolled at the Naples Conservatory and studied piano and composition. In 1876, Leoncavallo relocated to Bologna and began work on a triptych about the Italian Renaissance entitled Crepusculum (Twilight) as an homage to Wagner’s Ring Cycle. While in Bologna he also attempted (unsuccessfully) to secure a premiere of his first complete opera Chatterton (based on the life of the poet Thomas Chatterton).

Leoncavallo moved to Cairo, then Paris where he accompanied singers in music halls and continued to compose. One Paris collaborator, baritone Victor Manuel, introduced him to Giulio Ricordi and encouraged him to Milan where he would eventually rub elbows with Ricordi, his protegé Puccini, and other prominent members of the Milanese operatic elite.

Librettist Giuseppe Adami (a collaborator of Puccini’s on La Rondine, Il Tabarro, and Turandot) once wrote of Leoncavallo:

“There was to be found to be hanging about the Casa Ricordi a plump young man, rather short of stature, with a quaff of black hair dangle over his forehead like a question mark. That quaff questioned the owner’s future. Did it lie in poetry or music? He couldn’t make his mind up either way.”

Leoncavallo did indeed try his hand at writing libretto and had such talent for the art that he was even brought in by Ricordi to do rewrites on Puccini’s Manon Lescaut.

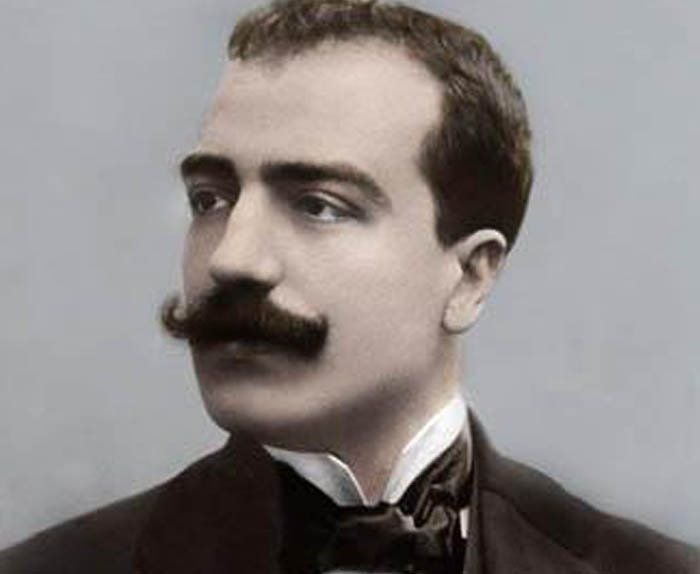

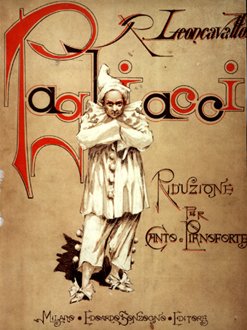

The Sonzogno Concorso of 1889 & Pagliacci

Ricordi’s primary competition in fin-de-siècle Milan was Eduardo Sonzogno’s publishing house. Sonzogno held a one-act opera composition competition in 1889 which was won by Pietro Mascagni with his naturalist tale of love and murder Cavelleria Rusticana. Using Mascagni’s hit as a dramatic and musical template, Leoncavallo set Crepusculum aside and penned his own scenario (originally also a one-act) based on passion and murder and based (at least partially) on a real life case that his father oversaw when Leoncavallo was a child. Ruggiero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci not only met, but surpassed the popularity of Cavellerìa Rusticana and the Cav/Pag double bill was born. Mascagni’s triumph and Leoncavallo’s follow-up changed the Italian operatic soundworld and birthed a musical movement. The verismo movement would come to dominate the standard operatic repertory worldwide for years and years to come.

The success of Pagliacci (1892) opened doors for Leoncavallo, who was then able to produce and premiere works such as I Medici (1893) - the only entry of the Crepusculum triptych to be completed, Chatterton (1896), La Bohème (1897), and Zazà in 1900.

The Two Bohèmes

In 1893, Puccini was setting his sights on his next big project as he was finishing his critically acclaimed opera Manon Lescaut. He opted to adapt Murger’s now-popular story of lovable Parisian misfits, Scènes de la Vie de Bohème. After receiving an initial sketch from his librettist and getting the go-ahead from his publisher, Puccini was ready to go full steam ahead with his next major production until he stumbled into one of the most ill-fated coffee dates in music history.

Puccini bumped into his longtime friend Leoncavallo at a cafe in the Milan in March of 1893. As fellow Italian opera composers, the relationship between the two had been very amicable until recent history changed their dynamic. Only one year prior, Leoncavallo achieved super-stardom in composing what would become his best-known work, Pagliacci. As a result, Leoncavallo unknowingly became one of Puccini’s rivals.

While exchanging pleasantries at the cafe, Puccini and Leoncavallo came to the awkward realization that they were both working on an opera adaptation of Bohème, but instead of musing about the coincidence, Leoncavallo became furious.

He reminded Puccini that he had offered him the libretto for his Bohème the year before, which Puccini had turned down. Although Puccini vehemently denied this, Leoncavallo couldn’t be dissuaded from thinking the worst: Puccini had declined an opportunity to collaborate with his former friend in favor of stealthily attempting to make his own version of the work.

Leoncavallo was so certain of his accusations that he used his ties with the local press to release multiple public statements, preemptively putting Puccini on blast. In one of the press releases, Leoncavallo even said that Puccini “confessed” to him that he came up with the idea to adapt Bohème only after Leoncavallo had already started working on his project.

Puccini fired back, publicly writing “what does it matter to Maestro Leoncavallo? Let him compose, I will compose. The audience will decide.” Puccini also made it abundantly clear that he had been working on Bohème for a mere two months, meaning that there was no long-con being executed behind the curtain.

But this wasn’t exactly true.

In 1926, two years after Puccini’s death, one of his friends and a former neighbor, Ferruccio Pagni and Guido Marotti (respectively), released a book of recollections about the composer called Puccini intimo. In the book, Pagni and Marotti remember that Puccini—despite unabashedly denying it in 1893—totally was offered Leoncavallo’s libretto for Bohème in '92 and had turned it down, just as Leoncavallo had said.

American biographer Mary Jane Phillips-Matz believes the circumstances of Puccini’s then-reported progress on Bohème to be suspect as well. Although Puccini said he had been working on the project for two months prior to his meeting with Leoncavallo, it’s clear from surviving letters to one of his librettists that the opera was in production for far longer than that. Musicologist Charles Osborne notes that it’s actually “quite likely” that Puccini stole inspiration from Leoncavallo, and that having a rival composer working on an enviable project was probably reason enough to ignite Puccini’s infamously competitive attitude.

The Bohème intellectual property was in the French public domain, so neither Puccini or Leoncavallo had any legal right to exclusivity. Creatively, it was up for grabs, so Puccini didn’t do anything wrong per se. While both operas eventually premiered, only one became a cornerstone of today’s operatic repertoire.

Story Credit: Joshua Figueroa

Zazà

Leoncavallo’s reputation today is one of a “one-hit-wonder” but it is worth noting that his successes were often in the hands of the critics that wrote for the music journals. It is well-known that the critics of the time were Verdi devotees and slow to accept the sonic innovations of the giovane scuola and the verismo movement. Also, many of the journals saw it as treachery when Leoncavallo signed with Casa Sonzogno rather than publish with his longtime “collaborator” Giulio Ricordi.

Leoncavallo’s fifth opera Zazà also had great, albeit temporary, international success for over two decades beyond its premiere in 1900. It was staged at the Met in New York City in 1920 for three consecutive seasons and was even chosen as iconic soprano Geraldine Farrar’s farewell performance in 1922.

Zazà is based on the Pierre Berton/Charles Simon play of the same name, which did very well at the Paris Vaudeville in 1898. Zazà had limited marketability because the compositional style was much more declamatory and not rounded into excerpt-able arias (which would have sold sheet music and raised awareness for the work.) Zazà was a very popular property for over thirty years with multiple theatrical and film adaptations.

Three versions of Zazà were published by Casa Sonzogno over the years. The Prima Edizione following the opera’s premiere in 1900, the Ultima Edizione in 1919: a streamlined version that eliminated much of the sonic hubbub of Act I as well as more efficient focus on the Zazà/Milio relationship development; and the 1947 Nuova Versione. This version abridged much of the non-essential plot points, the chorus, and several non-essential characters. This version was published by Casa Sonzogno nearly thirty years after the composer’s death and includes new realizations of certain musical moments by Renzo Bianchi. It also simplifies the vocal tessitura of the more demanding roles.

The Crane Opera Ensemble will be performing a version cut from sections of both the 1919 ultima edition and the 1947 nuova version. This was done in an effort to employ more of our talented singers in the Act I ensemble while still preserving the developing instruments of our young artists-in-training.

Zazà - The Crane Opera Ensemble

Join us this March 24-27, 2022 as The Crane Opera Ensemble puts Leoncavallo’s adaptation of Zazà on the Proscenium Theatre stage in the SUNY Potsdam Performing Arts Center. Also, stay tuned for blog entries exploring the visual influences for this production of Zazà as well as a deep dive into the social and psychological themes we’ll be exploring in this story.

Until next time,

A